A lot of things have happened since I last wrote something on here. I've been a little busy and lacked discipline to write my thoughts down consistently. Luckily I'm trapped on a flight without wifi - which is apparently what it takes.

So what happened in the world of Bitcoin in the past year and a half? Everything happened.

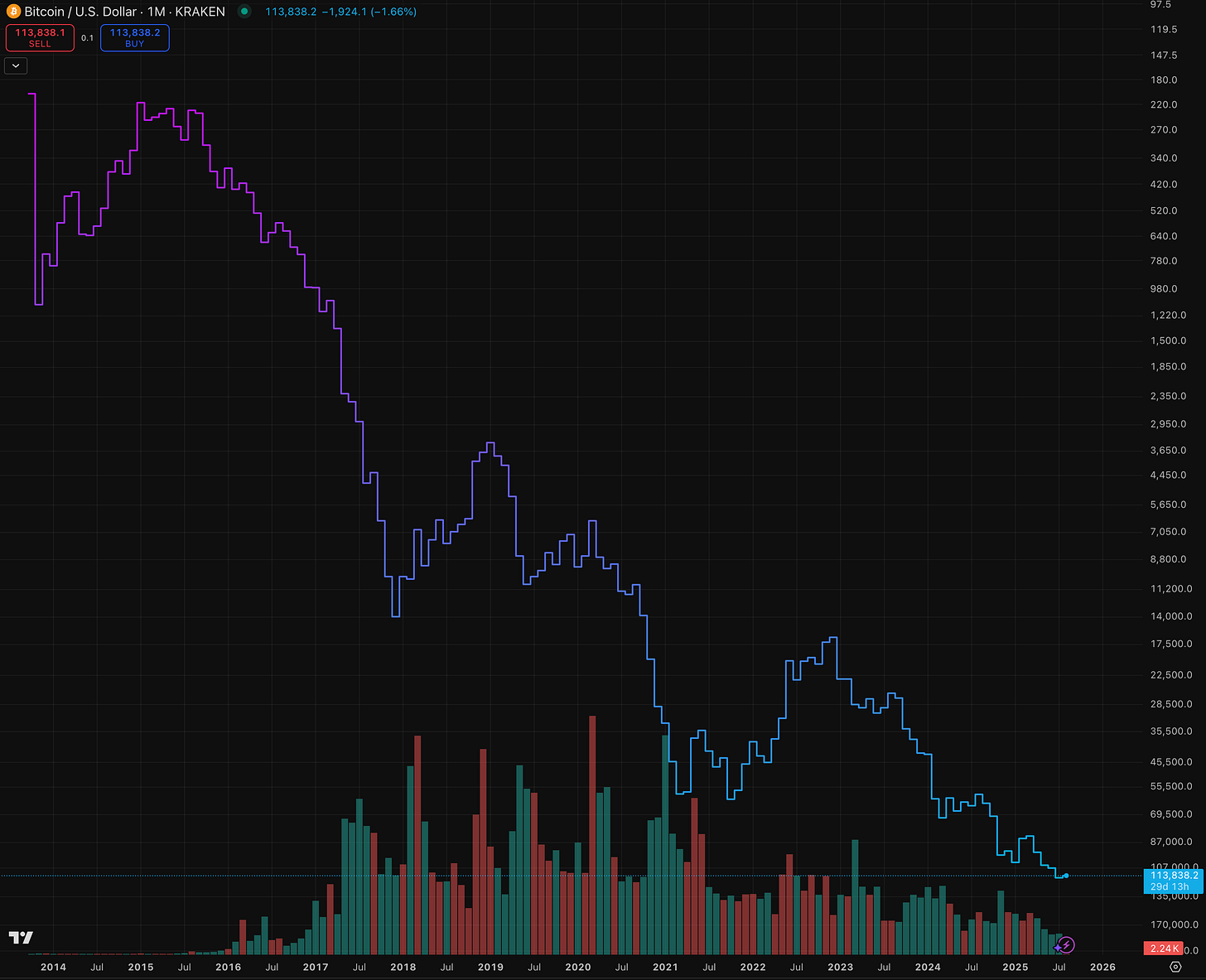

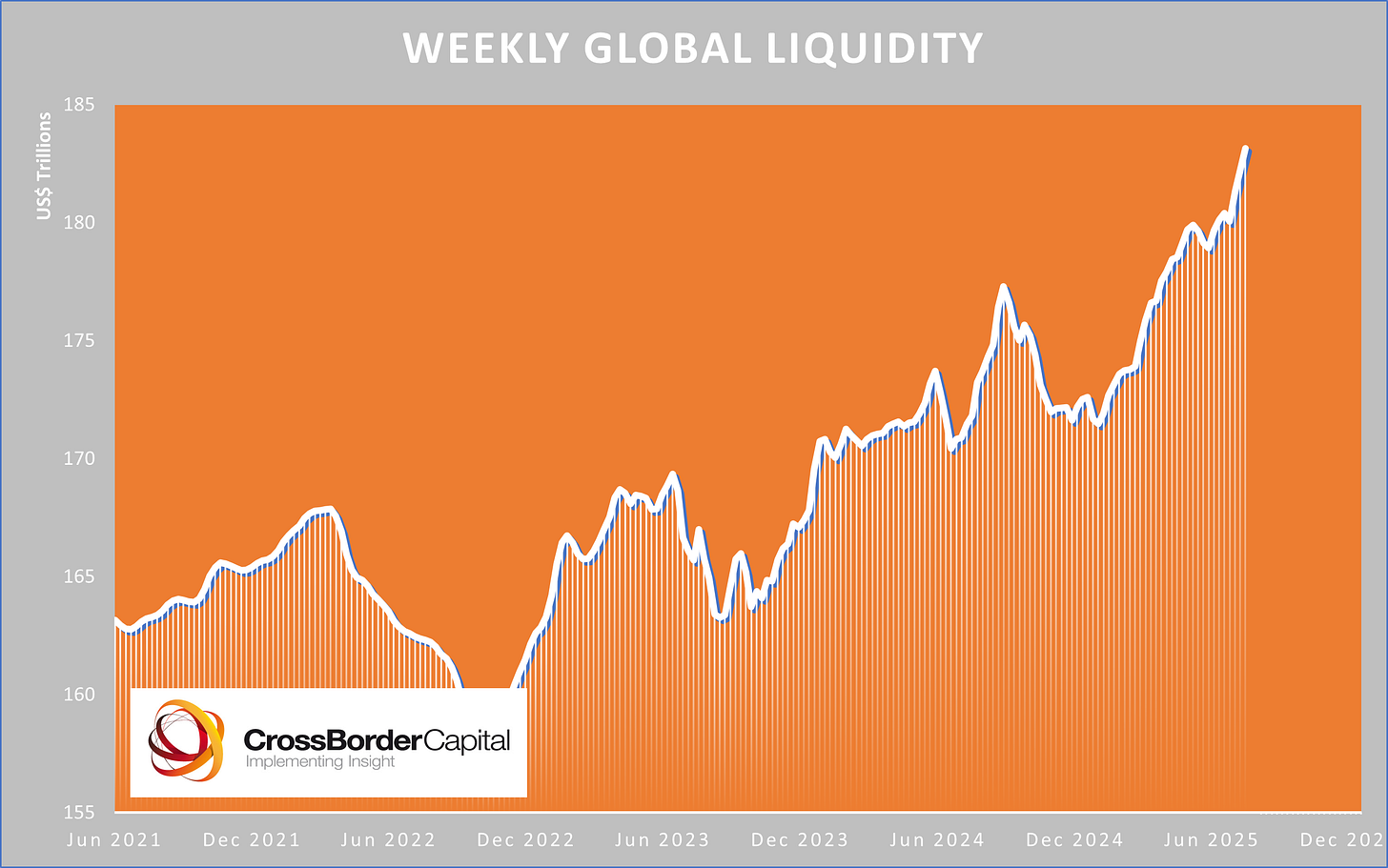

BTC broke $100k. The stock market loves Bitcoin. The US Administration is openly supporting Bitcoin as a reserve asset that ‘takes pressure off the dollar' (Trump). Most importantly, governments around the world continue to push global liquidity to all-time high after all-time high to fund their geopolitical ambitions. Former skeptics like JP Morgan now rush to issue BTC-backed loans and Bridgewater recommends a 15% portfolio allocation to monetary debasement hedges like Bitcoin.

The printer is back, and Bitcoin is fully mainstream.

That brings me to a question that I've been thinking a lot about lately - what's going to happen next? Hyperbitcoinisation? Is the world ready for that? How does something like that happen?

To hunt for answers, I reread my Oxford essays on the evolution of monetary systems. History is a great guide for the future.

The mainstream narrative in public discourse is currently something like this: monetary dominance is a function of Empire and Empires come and go.

The most popular example of this narrative is Ray Dalio's description of global financial empires. He starts with the Dutch Empire and the guilder, followed by the British Empire and sterling, which matured into the American Empire and dollar supremacy. Now that the US economy is an ever-shrinking share of the global economy, the American Empire either renews itself for the internet age or a new Empire and currency will take its place. It's a winner-take-all narrative.

Historical reality seems to suggest something different though. Financial Empires aren't winner-take-all; they overlap in messy, shifting layers.

History isn't so beautifully cyclical, but rather a messy picture where many Empires and reserve currencies coexist with one radically new reality following the other. Today's near-total dollar supremacy is actually highly novel, ahistorical almost. Modern financial commentators take today's dollar supremacy frame and slap it onto past and future Empires alike. This isn't very helpful and leads to unrealistic expectations for the future. If we want to say something useful about the future of Bitcoin, it would be a good idea to think about how financial supremacy worked historically.

It's important to understand that there was never one dominant reserve currency. Instead, history paints a fluctuating picture.

As a Dutch guy, I love how Ray Dalio has popularised the Dutch Empire's guilder as the early modern precursor to the dollar. It's fair to say that the Dutch invented financial empire as we know it today. The Republic was the most stable and predictable political system of its time and Amsterdam's rise to global superpower status showed the world what trust and capitalist free markets can achieve.

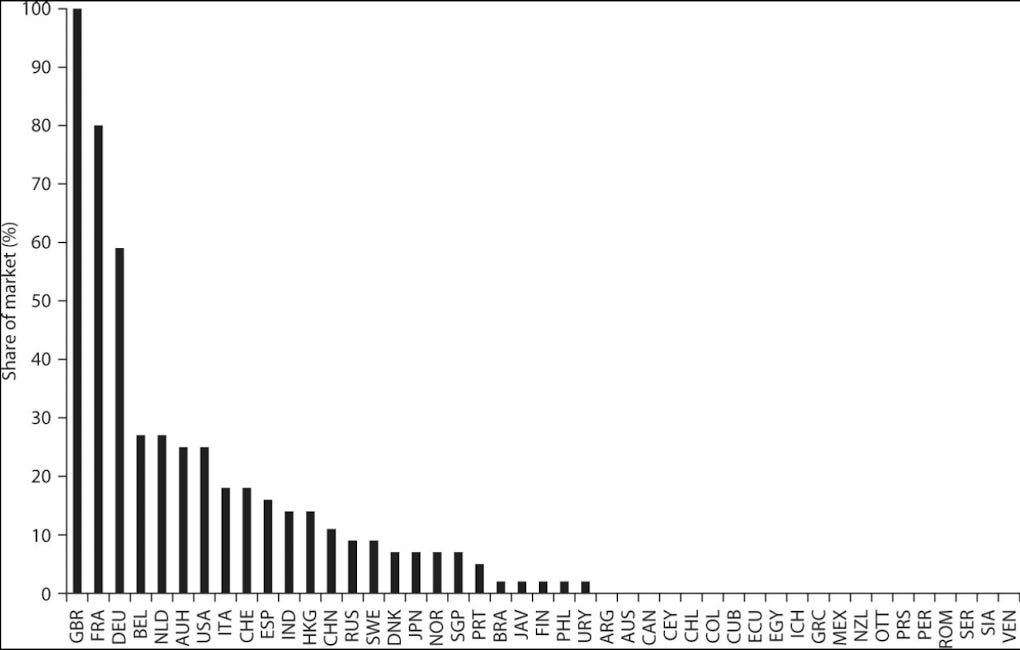

However, despite all this undisputed Golden Age greatness the guilder was nowhere near the dominant reserve currency. Amsterdam bills were found on about 60% of early modern foreign exchange markets. Paris and London bills were still found on 40% of markets as well, while Hamburg's bills reached 30% of markets. Amsterdam bills were preferred collateral as the most widely circulating bills by far, but not the winner-take-all global reserve asset.

The British Empire paints a similar picture. After copying many great Dutch inventions and adding even more scale, the British rose to superpower status in the mid-19th century thanks to trustworthy institutions and unparalleled depth of London's financial market. London cleared about 60% of global gold trade, and sterling debt paper became the go-to reserve. Yet sterling never monopolised the role.

After 1900, the fragmentation of global reserves accelerated as a result of capacity limits in London and the emergence of new alliances. With other countries now growing more rapidly than the more mature British economy, the British market was no longer large enough to accommodate the distress goods of other countries. The Baring crisis (when one of the most reputable London financial houses was pushed to the brink) already showed the limits of London as a financial centre. As the Boer War raged on in the early 1900s, confidence in convertibility of sterling debt into gold took a hit. This inaugurated a move back into hoarding gold and debt paper of closer allies. The Habsburg Empire chose to move an increasing amount of reserves into German paper, while the Russians shifted significant reserves to Entente ally France.

In light of these late British Empire developments, we can also better understand the world we live in today. Similar to London in the early 20th century, New York showed clear capacity limits to shoulder the weight of global reserves in 2008.

After the Soviet Union fell, hyper-globalisation sparked an insatiable appetite for first-class dollar-denominated debt. To satisfy demand, US banks climbed the risk ladder, securitising ever riskier assets, until things snapped. 2008 isn't a story of American greed. It’s a story of a financial market pushed to its limit.

The Trump administration intuitively understands this. When the rest of the world grows too large compared to the global economic centre, financial Empire becomes a liability. Rather than doubling down on Empire, it makes more sense to sacrifice Empire for national greatness. Former imperial subjects like Japan and the EU now become free-riders who have to pay their 'fair share'. In this context, reserve assets like gold and Bitcoin are no longer a threat to America. They serve as a release valve, easing pressure on domestic financial markets - just like investing in dollar-denominated assets took pressure away from emerging economies and allowed them to grow faster.

Diversification follows political friction; today is no exception. To hedge risk, it now makes sense to look beyond US paper - just like the Germans, Russians and Habsburgs looked beyond sterling paper from 1900.

So where are we going?

Well, we're likely headed towards a muddled financial future with diversification in reserves while the dollar still leads because of a lack of a viable alternative. Similar to Amsterdam balances remaining preferred reserves for their trust far past the peak of Dutch Empire into the 18th century, dollar-denominated assets will continue to dominate while Europe stagnates further and China keeps Stalinist control of its market.

We will hold dollar-denominated assets not because we believe in American Empire, but because we don't trust any of the alternatives. Meanwhile, BTC will continue to appreciate against USD and build ever deeper globally accessible liquidity against dollar-stablecoins on the internet. As trust in America continues to erode, the premium on mathematical trust and verifiability of BTC as a reserve asset automatically widens. In this world, the price target for BTC is infinite.

I expect a true paradigm shift towards full Bitcoinisation to happen as the world transitions to a fully AI-powered internet economy. Today's small economy of on-chain businesses already holds reserves in a basket of dollar-stablecoins and on-chain native assets like BTC. When fiat debasement is happening in plain sight, stashing excess reserves in a depreciating currency makes little sense - especially when you're a superintelligent AI natively deployed on the internet.

Sterling balances were useful for globally exporting American firms in the early 20th century, but a transition towards the native currency became top priority as soon as the global power structure allowed. Just like the rise of the American economy he was unstoppable in the eyes of early 20th century commentators, the rise of the internet is unstoppable today. The larger the internet economy becomes, the more likely a transition to an internet native reserve will become. Once something becomes a clear historical inevitability on a still unclear timeline, it usually just takes one catalyst for the timeline to become clear.

"There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen." — Lenin